There is nothing more practical than good theory

|

Victor Padilla-Taylor ‘15 is the Director of Mentor, Advisor and Partner Networks at the Tsai Center for Innovative Thinking at Yale (Tsai CITY). He is also a member of the Executive Advisory Board of the Global Consortium of Entrepreneurship Centers (GCEC), the Yale SOM Campaign Committee, and Director-at-Large of the SOM Alumni Advisory Board.

What’s a global trend you are following where you see an opportunity or bright spot in this challenging macro environment? In a world marked by wars, political division, climate concerns, and soaring living costs, I still feel optimistic when I see how we bounced back after COVID-19 with a longing for physical interaction. Let me explain: during our shared global struggle, we adopted a digital shift in our lives that made many pundits and experts announce the death of in-person education and the daily commute to work. We seemed to be heading to a ‘Zoom-ified’ world in life, school, and work. But virtual interactions could not fully replace face-to-face encounters when searching for genuine human engagement. Post-quarantine, learners around the world, including our Yale students, expressed a strong preference for in-person engagements over hybrid or virtual alternatives. Employers too noticed challenges in maintaining company culture and effective communication in a remote setup. I think that we’ve realized the irreplaceable value of physical presence and human connection, even if we keep some of the convenience gained through remote technologies. Thanks to online commerce and expanded service delivery, I don't find myself particularly nostalgic for my pre-pandemic supermarket routine. I truly appreciate, though, how these new automated aspects of my life have opened room and time to engage and indulge with others through partnerships, mentorships, creative pursuits, learning endeavors, meaningful conversations, and personal growth opportunities. This scenario highlights the irreplaceable value of genuine human engagement amidst the ever-expanding digital lives we have. What’s an example of how SOM’s mission informed the way you build teams or drive strategies in your professional life? I enjoy forming multi-stakeholder partnerships addressing complex challenges and combining seemingly incompatible goals. Currently, I support the development of startups, corporate, and social organizations connected to the larger entrepreneurial ecosystem at Yale. Priorly, I also led global actors from business and society to support humanitarian efforts to benefit ordinary people paying the unacceptable price of wars, displacement, famine, and natural disasters. Over the years, I have seen the school do the same beyond the lecture halls. And that keeps me motivated and committed to the mission. For example, the Global Network for Advanced Management (GNAM), created in 2012 by a consortium of leading business schools, has had SOM as a pivotal partner since its conception. This consortium believes in the power of networked learning, networked inquiry, and networked education, to increase collective intelligence, shared resources, and bring individuals with diverse perspectives, experiences, and knowledge to amplify positive impacts. Another example is SOM’s Program of Entrepreneurship, launched the year I joined the SOM Community in 2014. The program has grown significantly since its establishment to currently provide twenty different elective courses to students who want to lead for-profit and not-for-profit ventures that capture the attention of consumers, users, and society in general. Case in point, the student startup Banofi Leather recently took home the Prestigious Hult Prize for Sustainability of $1 million for its plan to turn banana crop waste into a sustainable leather alternative that can help offset the fashion industry’s environmental footprint. In a nutshell, SOM has not only equipped me and other leaders to serve business and society but has also demonstrated meaningful examples of how to bridge gaps, value diverse viewpoints, and excel across various disciplines. What’s an SOM experience that helped shape the way you understand business and society? During a long afternoon at Evans Hall in 2015, I remember doing ‘a Power Walk exercise’ as part of a class called ‘Interpersonal and Group Dynamics’. The goal of the exercise was to create ‘group socio-metrics’ using a series of questions to divide our class. Placed shoulder-to-shoulder, we were instructed to take a step if we agreed/identified with a statement, such as: you feel that you are a valued member of your community; you ate at least two full meals a day when you were a child; or, you have one parent who did not finish secondary school. After about 20 or 25 of these very personal questions, we all learned in silence to see how others had felt ‘power’ differently in their lives, whether they had or not the agency to make their own decisions about it. This exercise humanized us and opened our perspectives. At present, I do something similar with my students at Yale using a “creative tensions exercise”, which I also use to help them consider ‘perspective-taking’ and ‘empathic design’ amongst their fellow students, some innovators, leaders, and pioneers, and others creators, activists, and entrepreneurs from all fields and disciplines on campus. This exercise helps me facilitate an empathic conversation by asking questions that split the group into subgroups at each side of an issue. In a playful way, I can demonstrate a much-needed skill for new ventures seeking to create innovative solutions for real-world problems. It is with perspective-taking that founders can really understand what their customers need and want, and how teams can become capable of changing quickly in fast-paced environments, while embracing the mix of human beings with different ideas and experiences to ours that is often needed to do great things. As an international student, I remember how difficult it was for me to stay focused on my goal to expand my capacity to learn, live, and work outside of my home country. I needed help, and I quickly found it at SOM with a close-knit community of peers, faculty and staff members who were there for me and my challenges and taught me ‘perspective-taking’. With their support, I was able to understand how others may have a better view of challenges and opportunities. Since then, I have been able to not only adapt to new behaviors but also develop new attitudes and be more creative and less egocentric in my approach to work and relationships. What’s a favorite SOM memory, faculty member, mentor or class? I always share with incoming students at SOM that my favorite class during school was Interpersonal and Group Dynamics, taught by Heidi Brooks, Senior Lecturer in Organizational Behavior. As I mentioned earlier, for an international student and professional like myself, gaining the ability to 'learn through experience' marked a fundamental shift in my approach to life and personal development. The impact of this course in my life left me hungrier and led me to continue assisting Professor Brooks after graduation for five more years as a group facilitator. ‘What happened?’, ‘What was your response and reaction?’, ‘How do I make sense of the experience?’, and ‘What do I learn from this for next week?’ – I have repeatedly used all these questions and they have helped me move forward through this immense experiential lab we call ‘life’. If you want to learn more about how to cultivate the capacity to learn through experience, I recommend checking out Heidi Brooks’ new podcast here. I hope that you will love it as I do! What are you excited about for the year ahead? The SOMConnect Mentorship Program for students is launching in November 2023 and I’m excited about the impact this platform will have across the SOM community. The school is looking for SOM alumni to support it. To join the program, follow this link if you are already onboarded in SOMConnect, the school’s new digital alumni engagement platform. If you have not still joined, you can activate your account using this link. Mentorships are a great way to gain mastery in the art of perspective-taking. Without the support of so many who mentored me while I was an SOM student, I wouldn’t have been able to achieve the goals, growth, and milestones that have marked my professional journey. Our mentorship support can create immeasurable value for young professionals preparing for the challenges of business and society. The gratitude you will receive from these emerging leaders will be a testament to your service. Let’s walk this path together! Be a mentor today! Originally posted in the Yale SOM Alumni Blog -

0 Comments

It is easy to seek success and neglect our own physical and mental health. Many of us have been conditioned to believe that the only way to achieve our goals is to work hard, often at the expense of our physical and mental health. However, common sense and research suggests that a balanced life is essential for long-term success and happiness.

Drive to Survive To succeed in today's competitive environment, we need to be driven and focused. We need to be willing to take risks, push ourselves out of our comfort zones, and work tirelessly towards our goals. However, this drive should not cost us our well-being. It is essential to find a balance between our work and our personal lives, to ensure that we can maintain our energy and enthusiasm for the long haul. One way to achieve this balance is to set clear priorities and boundaries around our time and energy. We need to be mindful of our own limits and learn to say no when we are feeling overwhelmed. It is also important to take breaks when we need them, to recharge our batteries and come back to our work with renewed focus and energy. Just Be Kind While it is important to be driven and focused, it is equally important to be kind to ourselves. We need to recognize that we are human beings, not machines, and that we need time to rest and recharge. We will have the energy and resilience to face the hurdles of life if we do so. One way to unwind and be kind to ourselves is to focus on activities outside of work that lead us to be fulfilled. This could be spending time with family and friends, pursuing a hobby or passion, or simply taking time to relax and recharge. The Importance of Empathy Another key component of a balanced life is empathy. Satya Nadella says that 'success comes from empathy". If empathy is the 'action to understanding and being aware (even vicariously) of the experience, feelings, and thoughts of others' [Merriam-Webster], then it is essential for building strong relationships and also creating a positive culture at work. One way to develop empathy is to practice active listening. When we listen attentively to others, we show them that we value their thoughts and feelings. We can also put ourselves in their shoes and try to imagine how they might be feeling. By doing so, we can develop a deeper understanding of their experiences and perspectives. The Power of Mindfulness Finally, mindfulness is another powerful tool for achieving balance and well-being. Mindfulness helps us to be present and engaged where we are. Being mindful people helps us manage stress, reduce anxieties, and increase our overall sense of well-being. One way to cultivate mindfulness is to practice meditation or other mindfulness exercises. These practices can help us to quiet our minds and focus our attention on the present moment. They can also help us to develop a greater sense of self-awareness and improve our ability to manage our thoughts and emotions. In conclusion, a balanced life is essential for long-term success and happiness. By finding a balance between drive and self-care, we can achieve our goals while also maintaining our physical and mental well-being. By cultivating empathy and mindfulness, we can create a positive work culture, and build strong relationships with others. So, whether you prefer to "drive to survive" or "unwind to be kind," remember that a balanced life is within your reach. RESOURCES: Check out this FREE resource for meditation: www.uclahealth.org/programs/marc/free-guided-meditations/getting-started After months of hard work, 'We cross campus'. Yale alums and students can how meet more effectively through Cross Campus: Yale’s new, online networking, community-building, and mentoringplatform. In these hard times, Cross Campus draws Yale’s community closer through exchanges of advice, wisdom, and ideas. Alums share what they’ve learned. Students and alums can network, get advice, and get one-on-one coaching from Yalies who have “been in their shoes.” It’s powered by PeopleGrove, an expert in the field, and features ways to engage with Yale: through mentorship, either as a mentor or a mentee; with one-time advice; via an online discussion board to ask questions of fellow Cross Campus users; and by joining groups of interest. Cross Campus also features links to Yale affiliates and resources to help navigate the website, to make the most of being a Cross Campus member, and to be the best mentor or mentee you can be. During this pandemic, our new online community can help Yalies in a number of ways. For example, Cross Campus can provide a platform for people to connect with each other, share information and support, and exchange ideas and resources. Volunteers can particularly find new connections and knowledge to reach out to others in need. The overal effect will be less feelings of isolation and loneliness, and the creation of a sense of community and belonging during this difficult time. As this platform is particularly tailored for mentors and mentees who participate in our mentoring programs, we hope for the following benefits will come to our comunity:

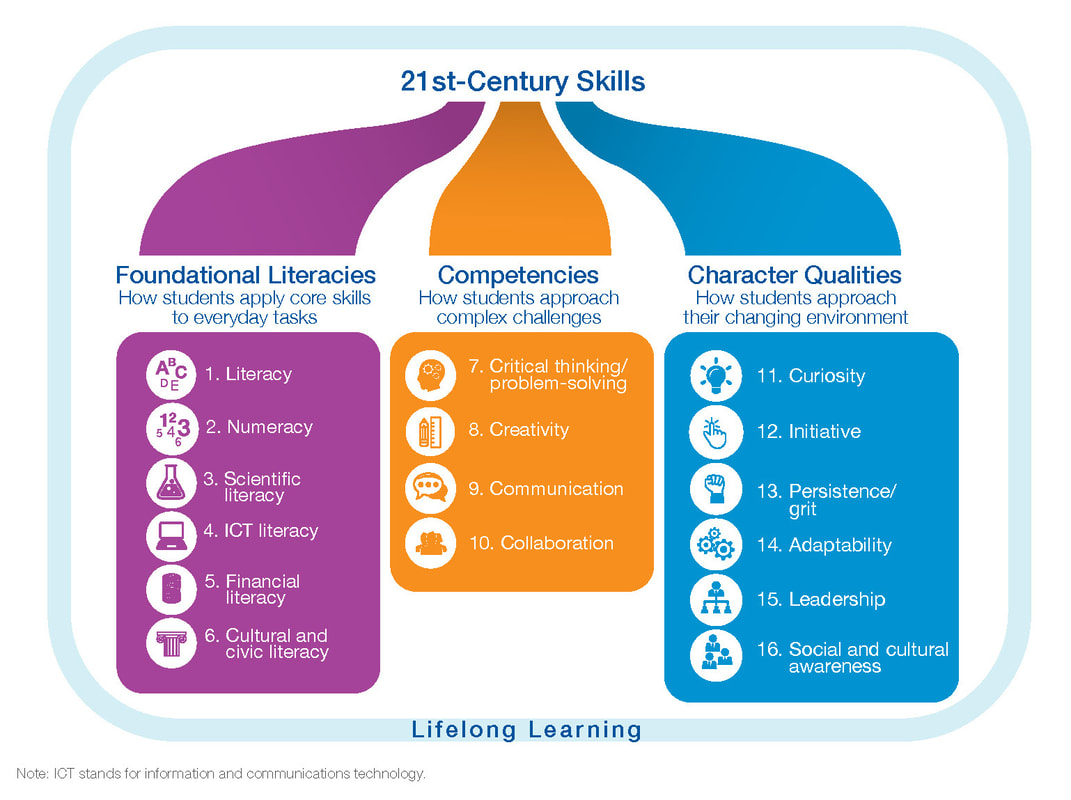

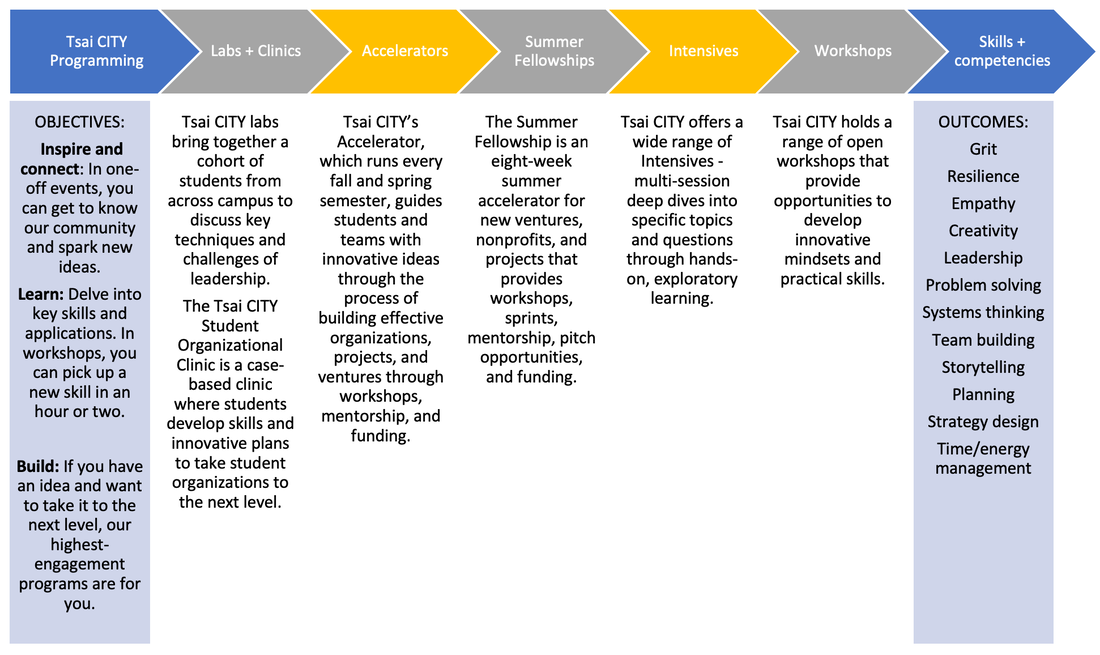

I have a brother who works at a call center in Guatemala. But his job will be replaced by artificial intelligence. Or maybe it already has been, since he told me recently of his training for a new position at his job. He used to click on screens and read scripts all day, almost unconsciously acting like a machine. Now that technology has caught up in this sector and his skills may not be needed anymore, he has to figure out his shortest re-skilling path to a new job in the future. This is an example of how artificial intelligence (or AI) is transforming our jobs in the 21st century. Last year, the McKinsey Global Institute found that artificial intelligence skills in the workforce grew 190% from 2015 to 2017. In their report, the firm showed that six of the 15 emerging jobs had some connection to AI.¹ With “machines taking over the world” in this way, many of us rightly fear that this trend can create a shortage of jobs in every industry and country around the world. But the reality is different. After some exploration, what we really find is a global shortage of skills², which simultaneously creates the chance for many workers today to benefit from this opportunity — provided that they receive proper training to seize it. However, key stakeholders in society need to invest even more in the training of current workers to get them ready for the future. Colleges and universities are doing their part to meet the need of re-skilling for the future. I am glad to see this because I have two college-age children at Yale University who are preparing for a future when conditions of work will definitely be fluid, and maybe even uncertain. As of 2017, according to the Global Consortium of Entrepreneurship Centres, more than 200 colleges and universities have launched centers for innovation or entrepreneurship³ to prepare their students for the future of work. This is good news for everyone. In agreement with my peers at the Tsai Center for Innovative Thinking at Yale (Tsai CITY), I strongly believe that entrepreneurial activity can teach us what the future of work might look like⁴ and how young generations can thrive in it. When students enroll in our programs, they not only expand their capacity to operate in today’s work environments, but also learn how to constantly update their skills as these environments evolve. Entrepreneurship teaches us to play, purposefully and not foolishly⁴, in today’s work environments. Students innovators trained at innovation centers can graduate ready for job markets, and not just for graduate school.⁵ When we teach our students to see their future jobs as bundles or agglomerations of skills, they can already start mastering these skills while they work on their innovative ideas on our campus. But we also make them aware of the fact that these bundles of skills can churn quickly⁶, so they can keep the constant need for re-skilling top of mind throughout their careers. Ginni Rometty, the CEO of IBM, shared at a World Economic Forum meeting this year that 100% of jobs in the world will change because of a crisis of skills and a context in which access to talent is more difficult than access to capital.⁷ We believe that student innovators will be ready for this new demand and will be intensely sought after in job marketplaces. Mastering technology The role of technology is key in this crisis of skills. It is not hard to see that today’s cutting-edge skills are just tomorrow’s mainstream requisites⁸(at best) because of the speed of technological development. But this is not the first time we have seen this occurrence. There have been already two mass extinctions of jobs caused by new technologies: in the hundred years that ended in 1970, the percentage of farm workers in the US decreased by 90%; between 1950 and 2010, the percentage of US factory workers decreased by 75%.⁹ So the question is: Will we see soon a new extinction of jobs due to the evolution of technologies like ride-hailing platforms, self-driving cars, and autonomous trucks? After all, “driver” is the most common job in 29 states of the U.S.⁹ If society does not provide these workers with proper opportunities to upgrade their skills, they may indeed become the new insecure precariat⁷ of the 21st century. This risk also extends to independent workers participating in the so-called “gig economy,” which accounts for almost 160 million people in the U.S. and fifteen major economies in the U.S. This number is almost 20–30% of the total working-age population, although governments statistics tell us that the number of independent workers is only around 11%.¹ Either way, we are talking about huge numbers of workers exposed to the risk of unemployment or underemployment because of a lack of employable skills. And the same situation happens throughout the rest of the world: Colombia and Vietnam report that 25% of their workforce is comprised of independent workers; Didi Chuxing in China employs 13 million drivers; Upwork connects 12 million freelancers to customers⁷; and ManpowerGroup finds jobs for 3.4 million people every year, half of whom are millennials.⁶ Therefore, perhaps the risk that these many workers face shouldn’t surprise us, although there is a genuine question whether new technological platforms create new jobs or if they are just capturing work that already existed offline.⁷ Will technology lead us down the path of a jobless future¹⁰ and a constant war over talent? I suggest that the war over talent is already here, as the process for the selection of Amazon’s second headquarters recently illustrated. As Mayor Sam Liccardo from San Jose, California, said, ignoring the bidding war altogether: “big companies like Amazon want to be where tech talent is.”² These somber considerations are too important to avoid. But technology shouldn’t necessarily be equated to an evil force, after all. Technology can be used for good or bad — just like in Star Wars, this “force” can be used for good or bad, and we can choose to become Jedi or Sith Masters.¹⁰ The question, then, is how we are thinking about the positive and negative systemic implications affecting a large portion of our working-age population. Maybe we want to see millions of drivers receive training to become the healthcare providers of the future.¹⁰ But, who would re-train this workforce? What will the cost be? And how will we pay the bill? Government and academia are expected players in this, but maybe the private sector can find an incentive to participate in this process. For example, whether drivers will share the upside of the coming Lyft or Uber IPO processes is an open question. Regardless, we would collectively need to consider how to transform these taxi and truck drivers into a new type of entrepreneurs, who are able to navigate the uncertainties of the future of work (many ride-hailing drivers already manifest an entrepreneurial spirit by multi-homing¹¹ across different platforms and taking risks to optimize their outcomes). In the future of work, a future when my own children will compete, learnability will determine their employability.⁶ Teaching innovation and entrepreneurship will be crucial for success. We will need to teach, however, a different kind of entrepreneurship that moves away from the behavior of badly reputed, hubris-filled entrepreneurs who dominate many headlines today.⁴ We need to move away from their zero-sum mentality⁴ and approach value generation and capture activities in a different way. We need more collaborative entrepreneurs who can think systemically. And this is why I am so excited to be a part of a team of mentors at Tsai CITY with fire in their belly for the education of the leaders of the future at Yale, through experimentation, re-skilling, and teaching emotional intelligence. The new building for the Tsai Center for Innovative Thinking at Yale: a playground-type, cutting-edge physical space for innovation David Deming, associate professor of education and economics at Harvard University, believes that the modern workplace resembles a pre-school classroom.¹² At Tsai CITY, we are supporting the playful (and purposeful) entrepreneurs that society and many job markets desperately need. We are teaching them to learn, re-skill, and play alongside other like-minded students seeking to address real-world problems affecting us all. In this era of artificial intelligence, we also see the need to double down on teaching emotional intelligence to our student innovators, with the goal of creating a healthier and more compassionate society.¹³ After all, the most important barriers to many entrepreneurs are not physical, educational, or financial, but psychological.¹⁴ As students learn to recognize, understand, label, express and regulate their emotions, they also learn to work more effectively in teams, while creating conditions and an environment to test new ideas, to fail, and to try again.

Endnotes

How do you build a mentor network that inspires students from all backgrounds and disciplines in the journey of innovation? We recently sat down with Victor Padilla-Taylor, Tsai CITY’s new Director of Mentor, Advisor, and Partner Networks, to get his perspective on this question. He shared how his personal journey — which has taken him from the highlands of his home country of Guatemala to the sand mountains in Saudi Arabia and back to the East Rock ridge in New Haven —will inform his work at CITY, as he aims to develop a supportive community of mentors that can meet students where they are in their own explorations of real-world problems and opportunities to solve them. Note: This interview was first posted on medium.com by Laura Mitchell. Tell us a bit about your new role at the Tsai Center for Innovative Thinking at Yale. My role as Director of Networks at our brand-new center involves connecting people (not computers, despite the title!) across Yale and beyond. When you think about the four actions that we promote here at CITY — inspire, learn, build, and connect — then you can understand that people come first in our community. My goal is to infuse interactions with excellence and to improve each day our students experience with the help of mentors, our partners across campus, and external advisors. What were you doing before joining the CITY team? Right before Tsai CITY, I was a Global Leadership Fellow at the World Economic Forum, an almost half-century-old institution that organizes the Annual Meeting at Davos. At this Swiss nonprofit with a global footprint, I learned the importance of private-public partnerships in creating solutions to systemic problems. I also saw how having diverse voices represented around the table can have a huge impact on the quality of solutions for real-world problems and how “acupuncture points,” or specific interventions, can be tested to change the current outcomes of global systems like trade, humanitarian assistance, and transportation. I have loved the nonprofit space and felt the call to do more than just generate profits since I graduated from the Yale School of Management (SOM) in 2015. Prior to SOM, I worked as an engineer in Latin America, also on networks — but networks of international suppliers and customers. One of the primary focuses of your role will be growing CITY’s mentor network. Why is mentorship an important component of CITY’s work? I think mentors are key to what we do at CITY because of the type of students we have at Yale: they are smart, they are creative, and they have big dreams. We have an opportunity to support these students as they work to find a path between their ideas and their big dreams. As mentors, we have a chance to inspire them through times of change, which often requires courage and resilience. We hope to build a mentor network with individuals full of passion for bridging gaps around big, real-world problems and also to help students learn what it takes to manage themselves. Success is not only about the outcomes of innovation as measured through money or actual products or services, but also about the outcomes of education: the development of new student mindsets and the resilience that’s crucial for sensible risk takers. In your view, what makes a great mentor? A great mentor is very good at listening before offering advice — I think it all starts with that. It also involves professional and personal disclosure and a willingness to unpack some of the useful baggage that has been accumulating throughout a life of experiences, successes and failures alike, which can be particularly helpful as lessons for students or teams working on taking their ideas to the next level. A third component I could add is caring for people enough to do the little things that are needed to help them move forward. Being a mentor at CITY is not just a job (most of our mentor positions are not paid). It is about loving the opportunity to work with students in their development process and being mindful about the place of influence you hold in their lives. As you get started in your role, what are you particularly excited to work on? First of all, I’m really excited to join the team at CITY. The university has brought together an all-star team, with people from so many different backgrounds and with so many different passions. And I’m also, of course, particularly thrilled about getting to know my extended team, the mentors in our network. A lot of work has been done with this community in the past year: just recently, for example, this network grew from 75 mentors to roughly 100. So I’m taking time to get to know these wonderful people and to see how we can better team up to deliver what our students need. Another thing I’m looking forward to is spending time with the partners we have on campus. They all have unique views of innovation within their spaces of expertise. And I am glad to see that most of them are thinking about innovation beyond apps and gadgets, often building on the university’s strengths in the humanities. I want to understand how they view innovation and mentorship in general, as well as how we can better support them. Embracing the different forms that innovation can take on campus, from the medical school to SOM to arts and drama, we can support a vision of common values and inclusion as One Yale. Beyond growing the mentor network, your role also involves working to build networks of advisors and partners. As CITY continues to grow, how do you envision it positioning itself in broader ecosystems?

Tsai CITY is meant to be a center of gravity for innovation at Yale. This is a nice metaphor that I have heard for a big mandate at the center. I certainly agree with it. The universe would be boring if it only had one sun and no planets, right? Yet it is also important to be more than just a collection of stars and planets: constellations are more beautiful. I think the great opportunity at our university is that we can interact and collaborate with other centers on campus to achieve even better outcomes. And we can also extend our influence beyond our campus borders to partner with peer institutions and other supporters around the world I personally envision CITY as a place where we meet our students where they are. By that I mean building a sort of base camp to support their innovation journeys, whether they’re just starting out and seeking information or are more advanced and need to access specific services, resources, or connections to players in specific fields. By growing our mentor network strategically — with experienced trekkers — I think we can achieve this. That’s my dream for CITY. How can people learn more and get involved? If you’re interested in mentoring, we have information on our website on how you can connect with us. Beyond that, nothing substitutes the warmth and quality of personal interactions, so even a phone call goes a long way. I’ll be venturing off campus to meet alumni and others interested in getting involved and will be encouraging one-on-one conversations with our partners and mentors-to-be, so that we can get to know each other and see where the best fits are. And of course, if anyone prefers email, I am reachable at [email protected]. And soon we will start building our new home! The construction of the new location for the Tsai Center for Innovative Thinking at Yale is slated to begin in December 2018. The new 12,500 square foot, two-story steel and glass building will be located at the southern end of the Becton Plaza behind the Yale Center for Engineering Innovation and Design, University Planner Kari Nordstrom wrote in a statement. The building will feature an open studio with a flexible configuration for different events, nine meeting rooms of various sizes, administrative offices and intimate areas to facilitate social interaction, Nordstrom added. Upon completion of the project, the building will seek Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design Gold certification, which is awarded to sustainable construction projects and buildings.

Source: Yale Daily News In a world that has turned more fractured than before, working at the World Economic Forum as a Global Leadership Fellow (GLF) has given me opportunities to re-evaluate globalization both at the existential and instrumental levels. At the existential level, I see a world that currently seems to be going back to tribalism. The Forum has responded directly to this trend by pointing out to the consequences of a world that moves away from shared values and interests. But there is another instrumental level where globalization is also being recalibrated: leadership and management styles are becoming more fluid because past and highly valued Western values are not recognized anymore as the only benchmarks for success. For every Apple and Facebook out there, there is an Alibaba and WeChat now.

In this context, the Forum has truly been a unique place of professional and personal learning that only a few other places in the world can also be. Every year, the Forum selects a few candidates amongst 6000+ applications to take part in its unique Global Leadership Fellows Programme, which combines intensive work with inspiring learning experiences around the world. The programme is developed in partnership with INSEAD, The Wharton School, Columbia University, London Business School, China Europe International Business School and THNK School of Creative Leadership over the course of three years. And its design and delivery are based on the «Agile Servant Leader» framework, which helps participants to develop self-awareness, a global mindset, contextual intelligence, and the ability to think and intervene systemically in business and societal issues. Grateful for this incredible opportunity, I graduated from the programme on May 2018 with an Executive Master's in Global Leadership. As a Global Leadership Fellow (GLF), I have changed multiple times my management roles and styles to serve many of our diverse communities. After all, I knew back in 2015 that I had joined the Forum ‘to improve the state of the world’, not to improve the state of ‘my world’. And even though I also knew about the importance of multi-stakeholder collaboration, I quickly realized that the convening power of this international organization provided me with an incomparable opportunity to create sustainable impact where business and society meet and work together. I learned to ‘map the issues’ and to identify proper institutional interventions that have the power to make our global systems healthier. I learned systems leadership, its mindsets, approaches and tools. If you are a leader for business and society (this is the ‘motto’ of my business school at Yale University), there is no shortage of diversity of action at the Forum: from community engagement to project management; from idea generation to insight curation; and from content creation to knowledge dissemination. I feel grateful for the trust I received to add, not to extract, to the Forum’s mission. Some of this work was uncharted territory for me and I grew in awareness of my choices as I traveled the new roads. And some of this work brought opportunities and the agency to shape my outcomes, even when navigating ambiguous objectives and unclear limits. After taking detailed stock of my everyday hustle during the past three years, which came on top of four hours of daily commute time between my home in New Haven, Connecticut, and New York City, I truly feel proud about these achievements and about how I managed to ‘struggle well’: • I interacted with senior executives of complex partner accounts and convinced them to increase their level of engagement in Forum activities. • I learned to manage and consolidate the outputs of the Forum’s Global Agenda Council on the Future of Logistics and Supply Chains in 2015-2016, which also led my team to entrust me with an evolved version of this group of cross-industry experts: the Global Future Council on the Future of Mobility, whose 25 members I personally interviewed, nominated and onboarded. • I facilitated the public-private dialogue of experts from the Global Agenda Council with officials from the Government of Panama, which included a mission trip to the country to scope the activities needed to deploy a Logistics Control Tower. • As a facilitator of an impactful public-private partnership supporting the humanitarian community, I contributed to the expansion of activities of the Logistics Emergency Teams to include disaster preparedness in addition to its emergency response relief and assistance during complex crises. • I assisted the Logistics Emergency Teams during the 2017 flooding crisis in Peru by facilitating the coordination efforts between this partnership and the government. • I contributed to the design and delivery of a three-day training workshop in May 2017 for a group of employees of the Logistics Emergency Teams to prepare them to respond to natural disaster crises. • I participated in the creation and promotion of new narratives to communicate the efforts of the Logistics Emergency Teams activities. • I scoped the ideation of a new social impact project by organizing two sessions at Forum events (India Economic Summit 2016, Annual Meeting 2017) which ultimately led to its internal approval and support of two Forum Project Advisors who presented bids to launch my idea. • I coordinated internal Forum resources and those of Deloitte Consulting LLC to deliver the objectives for a project dealing with ‘transportation poverty’ (SIMSystem: Designing Seamless Integrated Mobility). • I organized three dynamic project workshops on ‘transportation interoperability’ in the cities of Berlin, New York and Japan; I also organized and delivered sessions at an Industry Strategy Officers meeting, two Annual Meetings, one Summit of Global Agenda Councils, two Summits of Global Future Councils and workshops at Mexico City (Enabling Trade), Miami and Dubai (LET training) and New York (launch of Community for Effective Humanitarian Response). • I coordinated the internal Forum resources and those of the consulting firm Bain & Company to deliver the objectives of a trade facilitation project (Enabling Trade: Unlocking the Potential of Mexico and Vietnam). • I presented the Enabling Trade Index framework to the Government of Mexico as an approach to their efforts to gain regulatory support for the implementation of the Bali trade agreement. • I supported the Head of Supply Chain and Transport in growing the Industry community of partner companies, Chief Executive Officers and Heads of Strategy • I contributed to the launch of the following publications: The New Silk Road, Idea and Concept; Digital Transformation of Industries, Logistics Industry; Enabling Trade, Unlocking the Potential of Mexico and Vietnam; How Technology Can Unlock the Growth Potential along the New Silk Road; Designing a Seamless Integrated Mobility System, A Manifesto for Transforming Passenger and Goods Mobility; Hurdles ahead along the “New Silk Road” (published in Financial Times), also published in the Forum’s Agenda website; “There's one wall Mexico could break down” (published in Business Insider). • I supported via coaching three female members of the Mobility team on the topic of constructive feedback. • I collaborated on the translation to Spanish of the First Edition of “The Fourth Industrial Revolution” book written by the Chairman Klaus Schwab; and • I collaborated with Human Resources to represent the Forum at recruiting events at Yale University. For all these activities, I became a quicker learner, more analytical, more tactful in my communications with others, a better listener and an active examiner of the truth. Often I needed to restrain my overconfidence and leave it out the door. But I recognize that I would not have been able to perform as described above, in the mature and tempered manner often required during stressful situations, without the support and guidance of internal and external coaches and mentors, colleagues and my GLF peers sharing this exciting journey. Now that I have graduated from the GLF programme, the year of 2018 finds me feeling more passionate about social impact. I hope to continue ‘connecting the dots’ between systemic issues with the help of my acquired systems thinking practice. I trust that with good communications skills, along with my improved storytelling, the next chapter will bring me closer to more opportunities to pitch internally and externally new ideas for the betterment of society. I have become a believer of the theory of change that system leaders encourage. Sustainable change is not about mission accomplished, it is about creating healthy systems. It is not just about seeing problems; it is also about recognizing patterns. And it is not just about planning and control; we need the capacity to learn and adapt. I want to continue traveling the journey of a systems leader, who acts holistically and moves away from compartmentalized approaches. Systems leaders push for the search of the hidden causes underneath the visible aspects of a problem, decipher its related trends through time and intervene with modest but carefully designed actions to achieve meaningful and sustainable impact. The world can be a place of discovery through the application of systems leadership. And this practice can help us give people a sense of agency, direction, hope and collective purpose. For this incredible journey, after assessing my numerous lessons learned, I clearly find that the World Economic Forum is truly a unique place for advanced contextual learning. The Fourth Industrial Revolution is characterized by the unprecedented advances in technology transforming the way individuals and groups across society live, work and interact. New principles, protocols, rules and policies are needed to accelerate the positive and inclusive impacts of these digital and technological transformations, while minimizing or eliminating their negative consequences.

|

AuthorVictor Padilla-Taylor is Director of Networks at the Tsai Center for Innovative Thinking at Yale. He was the 2021 recipient of the Linda Lorimer Award for Distinguished Service, conferred by Yale’s president on staff who have demonstrated their commitment to innovative thinking and the educational and research missions of the university. He also serves as board leader at Global Consortium for Entrepreneurship Centers, Long Wharf Theatre, Yale SOM Alumni Advisory Board, and Saint Thomas More Chapel and Center at Yale University. For his accomplishments as alumni volunteer, he received the 2023 Yale Alumni Leadership Award for his service and innovative leadership as nominated and selected by alumni relations staff members. AlpsBoundA global soul with MBA experience from GNAM schools around the world Archives

October 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed