There is nothing more practical than good theory

|

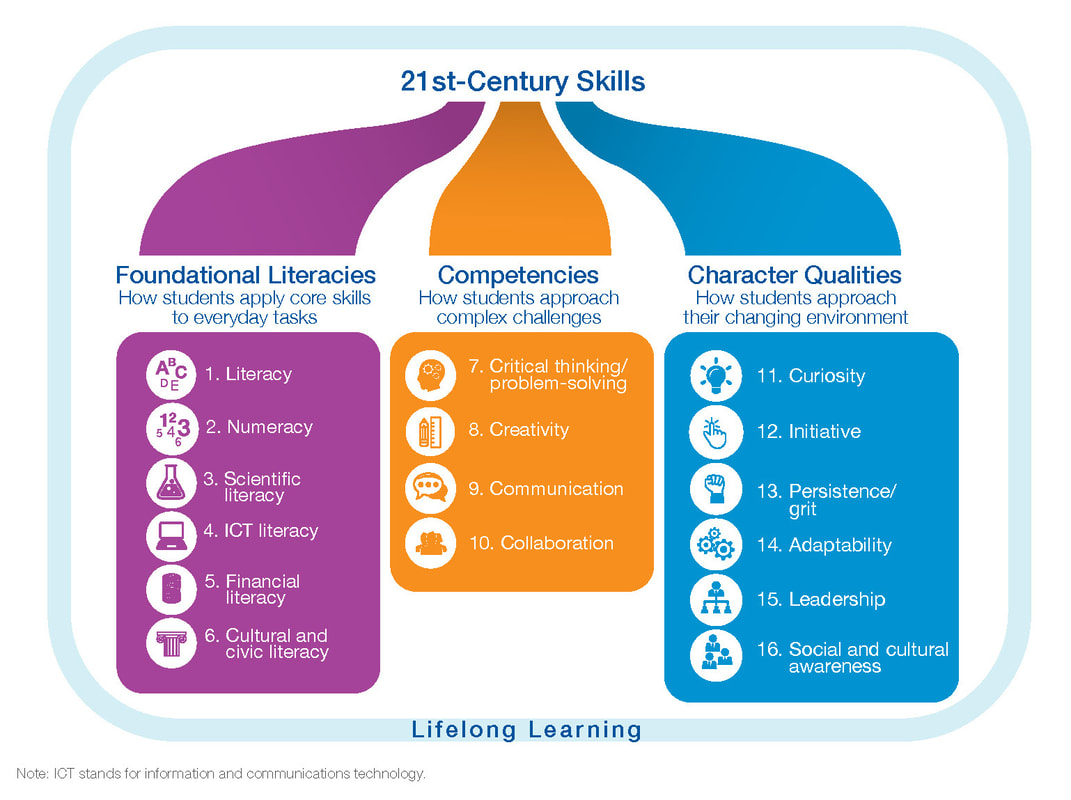

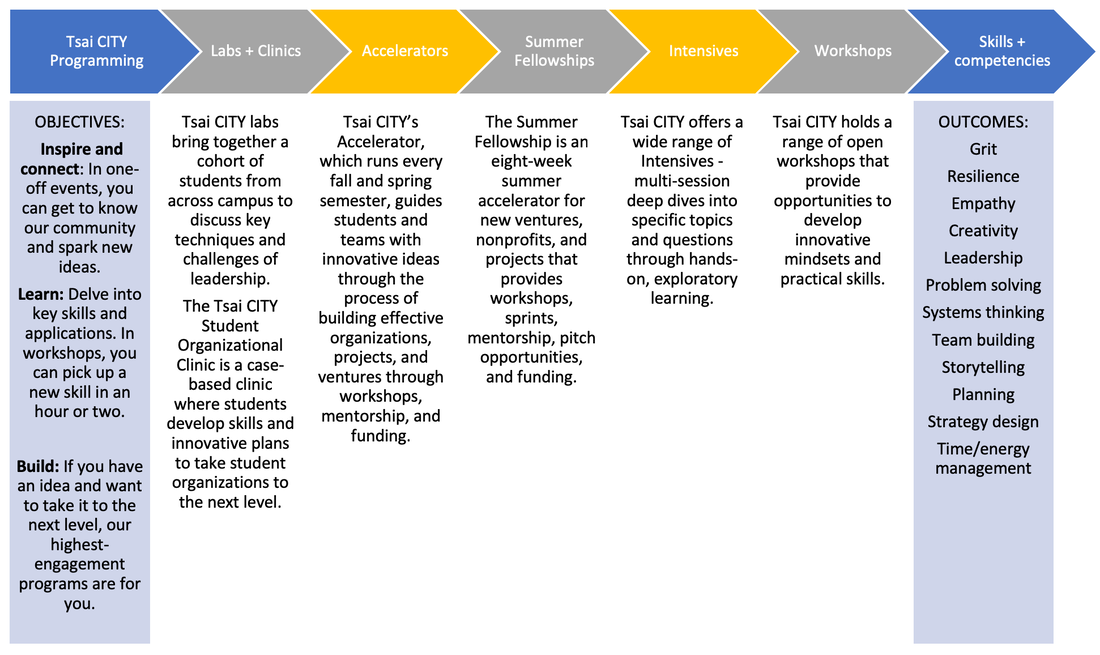

I have a brother who works at a call center in Guatemala. But his job will be replaced by artificial intelligence. Or maybe it already has been, since he told me recently of his training for a new position at his job. He used to click on screens and read scripts all day, almost unconsciously acting like a machine. Now that technology has caught up in this sector and his skills may not be needed anymore, he has to figure out his shortest re-skilling path to a new job in the future. This is an example of how artificial intelligence (or AI) is transforming our jobs in the 21st century. Last year, the McKinsey Global Institute found that artificial intelligence skills in the workforce grew 190% from 2015 to 2017. In their report, the firm showed that six of the 15 emerging jobs had some connection to AI.¹ With “machines taking over the world” in this way, many of us rightly fear that this trend can create a shortage of jobs in every industry and country around the world. But the reality is different. After some exploration, what we really find is a global shortage of skills², which simultaneously creates the chance for many workers today to benefit from this opportunity — provided that they receive proper training to seize it. However, key stakeholders in society need to invest even more in the training of current workers to get them ready for the future. Colleges and universities are doing their part to meet the need of re-skilling for the future. I am glad to see this because I have two college-age children at Yale University who are preparing for a future when conditions of work will definitely be fluid, and maybe even uncertain. As of 2017, according to the Global Consortium of Entrepreneurship Centres, more than 200 colleges and universities have launched centers for innovation or entrepreneurship³ to prepare their students for the future of work. This is good news for everyone. In agreement with my peers at the Tsai Center for Innovative Thinking at Yale (Tsai CITY), I strongly believe that entrepreneurial activity can teach us what the future of work might look like⁴ and how young generations can thrive in it. When students enroll in our programs, they not only expand their capacity to operate in today’s work environments, but also learn how to constantly update their skills as these environments evolve. Entrepreneurship teaches us to play, purposefully and not foolishly⁴, in today’s work environments. Students innovators trained at innovation centers can graduate ready for job markets, and not just for graduate school.⁵ When we teach our students to see their future jobs as bundles or agglomerations of skills, they can already start mastering these skills while they work on their innovative ideas on our campus. But we also make them aware of the fact that these bundles of skills can churn quickly⁶, so they can keep the constant need for re-skilling top of mind throughout their careers. Ginni Rometty, the CEO of IBM, shared at a World Economic Forum meeting this year that 100% of jobs in the world will change because of a crisis of skills and a context in which access to talent is more difficult than access to capital.⁷ We believe that student innovators will be ready for this new demand and will be intensely sought after in job marketplaces. Mastering technology The role of technology is key in this crisis of skills. It is not hard to see that today’s cutting-edge skills are just tomorrow’s mainstream requisites⁸(at best) because of the speed of technological development. But this is not the first time we have seen this occurrence. There have been already two mass extinctions of jobs caused by new technologies: in the hundred years that ended in 1970, the percentage of farm workers in the US decreased by 90%; between 1950 and 2010, the percentage of US factory workers decreased by 75%.⁹ So the question is: Will we see soon a new extinction of jobs due to the evolution of technologies like ride-hailing platforms, self-driving cars, and autonomous trucks? After all, “driver” is the most common job in 29 states of the U.S.⁹ If society does not provide these workers with proper opportunities to upgrade their skills, they may indeed become the new insecure precariat⁷ of the 21st century. This risk also extends to independent workers participating in the so-called “gig economy,” which accounts for almost 160 million people in the U.S. and fifteen major economies in the U.S. This number is almost 20–30% of the total working-age population, although governments statistics tell us that the number of independent workers is only around 11%.¹ Either way, we are talking about huge numbers of workers exposed to the risk of unemployment or underemployment because of a lack of employable skills. And the same situation happens throughout the rest of the world: Colombia and Vietnam report that 25% of their workforce is comprised of independent workers; Didi Chuxing in China employs 13 million drivers; Upwork connects 12 million freelancers to customers⁷; and ManpowerGroup finds jobs for 3.4 million people every year, half of whom are millennials.⁶ Therefore, perhaps the risk that these many workers face shouldn’t surprise us, although there is a genuine question whether new technological platforms create new jobs or if they are just capturing work that already existed offline.⁷ Will technology lead us down the path of a jobless future¹⁰ and a constant war over talent? I suggest that the war over talent is already here, as the process for the selection of Amazon’s second headquarters recently illustrated. As Mayor Sam Liccardo from San Jose, California, said, ignoring the bidding war altogether: “big companies like Amazon want to be where tech talent is.”² These somber considerations are too important to avoid. But technology shouldn’t necessarily be equated to an evil force, after all. Technology can be used for good or bad — just like in Star Wars, this “force” can be used for good or bad, and we can choose to become Jedi or Sith Masters.¹⁰ The question, then, is how we are thinking about the positive and negative systemic implications affecting a large portion of our working-age population. Maybe we want to see millions of drivers receive training to become the healthcare providers of the future.¹⁰ But, who would re-train this workforce? What will the cost be? And how will we pay the bill? Government and academia are expected players in this, but maybe the private sector can find an incentive to participate in this process. For example, whether drivers will share the upside of the coming Lyft or Uber IPO processes is an open question. Regardless, we would collectively need to consider how to transform these taxi and truck drivers into a new type of entrepreneurs, who are able to navigate the uncertainties of the future of work (many ride-hailing drivers already manifest an entrepreneurial spirit by multi-homing¹¹ across different platforms and taking risks to optimize their outcomes). In the future of work, a future when my own children will compete, learnability will determine their employability.⁶ Teaching innovation and entrepreneurship will be crucial for success. We will need to teach, however, a different kind of entrepreneurship that moves away from the behavior of badly reputed, hubris-filled entrepreneurs who dominate many headlines today.⁴ We need to move away from their zero-sum mentality⁴ and approach value generation and capture activities in a different way. We need more collaborative entrepreneurs who can think systemically. And this is why I am so excited to be a part of a team of mentors at Tsai CITY with fire in their belly for the education of the leaders of the future at Yale, through experimentation, re-skilling, and teaching emotional intelligence. The new building for the Tsai Center for Innovative Thinking at Yale: a playground-type, cutting-edge physical space for innovation David Deming, associate professor of education and economics at Harvard University, believes that the modern workplace resembles a pre-school classroom.¹² At Tsai CITY, we are supporting the playful (and purposeful) entrepreneurs that society and many job markets desperately need. We are teaching them to learn, re-skill, and play alongside other like-minded students seeking to address real-world problems affecting us all. In this era of artificial intelligence, we also see the need to double down on teaching emotional intelligence to our student innovators, with the goal of creating a healthier and more compassionate society.¹³ After all, the most important barriers to many entrepreneurs are not physical, educational, or financial, but psychological.¹⁴ As students learn to recognize, understand, label, express and regulate their emotions, they also learn to work more effectively in teams, while creating conditions and an environment to test new ideas, to fail, and to try again.

Endnotes

1 Comment

|

AuthorVictor Padilla-Taylor is Director of Networks at the Tsai Center for Innovative Thinking at Yale. He was the 2021 recipient of the Linda Lorimer Award for Distinguished Service, conferred by Yale’s president on staff who have demonstrated their commitment to innovative thinking and the educational and research missions of the university. He also serves as board leader at Global Consortium for Entrepreneurship Centers, Long Wharf Theatre, Yale SOM Alumni Advisory Board, and Saint Thomas More Chapel and Center at Yale University. For his accomplishments as alumni volunteer, he received the 2023 Yale Alumni Leadership Award for his service and innovative leadership as nominated and selected by alumni relations staff members. AlpsBoundA global soul with MBA experience from GNAM schools around the world Archives

October 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed